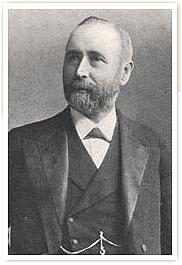

In 1862, a new gentleman apprentice began working in the draughting department at Harland and Wolff, a fifteen-year old lad of Canadian birth and Irish ancestry. His name was William James Pirrie.

In 1862, a new gentleman apprentice began working in the draughting department at Harland and Wolff, a fifteen-year old lad of Canadian birth and Irish ancestry. His name was William James Pirrie.

Pirrie was born in Canada, in the province of Quebec, the son of James and Eliza Pirrie. Two years after William’s birth, his father moved the family back to the Emerald Isle, settling in Conlig, County Down in Northern Ireland. Pirrie was educated at the Royal Belfast Academical Institution (a Belfast “grammar school”–what would be a private school in the United States–founding in 1811 which quickly established a reputation for academic excellence and from which Harland and Wolff would draw an impressive succession of engineers, managers and directors) before taking up his position at the shipyard as a gentleman apprentice in 1862. He married Margaret Carlisle, the sister of Alexander Carlisle, who would become one of Harland and Wolff’s most gifted marine architects, in 1879–together Pirrie and Carlisle would be the driving forces during the shipyard’s most prosperous years. Pirrie’s business acumen and organization skills were so exceptional that within twelve years of his joining Harland and Wolff he had become a partner in the firm; when Sir Edward Harland died in 1895, Pirrie succeeded him as chairman, a position he was to hold until his death. Under his direction, within ten years Harland and Wolff became the world’s largest shipyard, even expanding across the Irish Sea and setting up fabricators and manufactories along the Clyde in Scotland. The yard built vessels for a variety of British and foreign steamship companies, as well as constructing warships for the Royal Navy. Pirrie’s particular genius lay in introducing what amounted to “mass production” methods in shipbuilding, using, for example, standardized dimensions and sizes for the shell-plating and frame members, as well as standardizing equipment installed in the ships, which reduced labor and material costs along with construction time.

Pirrie was elected Lord Mayor of Belfast in 1896, and was made an Irish Privy Counsellor the following year. In 1906, at the height of Harland and Wolff’s success, he was given a life peerage as Baron Pirrie of the City of Belfast–fifteen years later he would be raised to the rank of Viscount. In 1907 he was appointed Comptroller of the Household to the Lord-Lieutenant of Ireland, and in 1908 was named a Knight of St Patrick (KP).

Though he had little to do directly with the construction of the Titanic once he and Bruce Ismay finalized the details of the Olympic-class ships’ design and appointments, Lord Pirrie had intended to be aboard the Titanic for her maiden voyage, but illness laid him low at the last minute, preventing him from joining the ship–and probably saving his life in the process. The reputation of the shipyard was little affected by the loss of the Titanic (Belfast folk are still proud of being able to say “The Titanic wasn’t a disaster, what happened to her was!”) and Pirrie remained a dynamic figure in Belfast, serving as Pro-Chancellor of the Queen’s University from 1908 to 1914, as well as sitting on the Committee on Irish Finance and serving as Lieutenant for the City of Belfast. During the Great War his organizational skills were at a premium, and as a member of the War Office Supply Board became Comptroller-General of Merchant Shipbuilding, overseeing and coordinating the construction of merchant ships in British shipyards.

After the war Pirrie remained active in Northern Ireland’s political scene, being elected to the Northern Irish Senate in 1921. He died of pneumonia at the age of 77, in June 1924, while on a business trip to South America. His body was brought back to Belfast aboard the Olympic.

One of the unexpected consequences of Lord Pirrie’s political activities was that when Belfast City Hall was being built from 1898 to 1906, he would often send skilled craftsmen from the shipyard–plasterers, wood carvers, joiners, painters–into the town to work on the new building. To this day Belfast City Hall is known as “the Stone Titanic” because so much of its interior decor was completed by men who had labored on the Olympic class ships, their distinctive styles of workmanship still being immediately recognizable today as identical to the craftsmanship put into the interiors of the Titanic and her sisters.

to work on the new building. To this day Belfast City Hall is known as “the Stone Titanic” because so much of its interior decor was completed by men who had labored on the Olympic class ships, their distinctive styles of workmanship still being immediately recognizable today as identical to the craftsmanship put into the interiors of the Titanic and her sisters.

For all of his accomplishments as the Chairman of Harland and Wolff during the shipyard’s most prosperous years, there was a dark side to Pirrie’s tenure. In Belfast stories are still told quietly–and sometimes not so quietly–of Pirrie keeping several sets of books in order to not only deceive British tax authorities, but also the other partners in the firm as to just how much money the shipyard was making, as well as concealing the skimming of profits by Pirrie himself as well as members of his family. After Pirrie’s death, the shipyard’s finances were in such disarray that it would take several years to sort them out, a situation that brought the firm to the brink of insolvency when the Great Depression hit in late 1929.